By Bob McNally

The 40 mile per hour boat run across Arkansas’ Lake Ouachita to the striper school was frantic and wild. The air temperature hovered at 20 degrees. All anglers aboard were bundled in thick down parkas, ski gloves, stocking caps, and insulated hunting boots. The wind during the boat run drove through our crew like an invisible icy spike.

But soon we were at the place where birds squawked and dove at baitfish that flitted about on the surface. Our group of four anglers each fired lures toward the bird-and-bait melee, and quickly everyone’s rod bowed tightly as heavyweight striped bass struck and ran deep.

For 10 minutes there was total pandemonium. More boats of anglers roared up to join the action. Birds screamed overhead. Fishermen laughed and shouted instructions to each other. Reel drags howled. Outboard motors coughed. And several dozen striped bass were hauled aboard the boats.

Then the action stopped as abruptly as it began. Birds disappeared, anglers dispersed, and the cold tranquility of the lake resumed.

This kind of striped bass angling is called “fishing the jumps.” It’s well-publicized action as exciting as fishing gets. The targets are big, bruising striped bass that slam lures like freight trains, and fight like pit bull terriers shaking rag dolls. They’re also pretty darn good on a dinner plate.

“Fishin’ the jumps” is common on many freshwater impoundments throughout America where striped bass are found. But such fishing is not available year-round. It’s best during the coldest, most chilling months of winter, and it’s best appreciated by hard-core anglers who can handle biting wind and icy weather. Frequently, ice forms on rod guides, and reel spools freeze. Cold, wet ears, noses, toes and hands are common.

“Jump fishing” is regularly practiced from December through March or April on many of America’s better striper fisheries. The most consistently good “jump fishing” usually is found at daybreak, dusk and during overcast weather. Standard technique is to run to the upper reaches of a lake, and drift near river channel edges while watching surrounding areas through binoculars. Anglers look for diving gulls, which signal when stripers drive baitfish topside. Then fishermen run wide open in boats to birds and cast lures before bait and stripers sound and disappear.

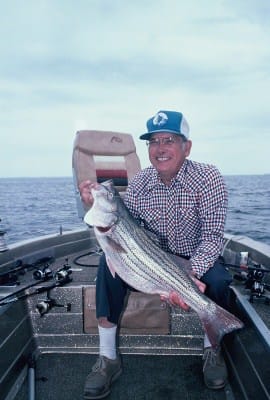

Just because “jump stripers” are in schools doesn’t mean they’re not big. Many winter “jump” stripers average 5 to 12 pounds, but 20- to 30-pound fish are not uncommon on many waters.

Many winter “jump fisherman” use jigs almost exclusively.

Experts commonly favor plastic-tail white or silver grubs or white bucktails in 3/8-ounce to 5/8-ounce models. At times birds reveal where stripers are holding, but the fish and bait do not come topside. This is when slow, deep jigging is mandated. For this kind of “striper prospecting” it’s often a good idea to tip jigs with live shiners, herring, shad or similar baitfish native to the water, since it aids tempting deep stripers into striking.

If linsiders are particularly finicky, nothing takes more stripers or bigger ones in winter, than live baits soaked deep. Anglers watch for gulls and run boats to them the same way as when “fishin’ the jumps.” But instead of casting lures, they shut down motors upwind of birds and drift baits deep, or move in quietly with electric motors.

Deep trolling with downriggers and live baits, plugs and spoons also is deadly mid-winter striper medicine. But waters must have a “clean,” uncluttered bottom (no timber or stumps) for the most effective downrigger work.

Stripers are common on many reservoirs or man-made impoundments throughout much of America. In such waters, winter stripers usually hold just off the bottom or suspend over river bed channels, sunken island structures, or in flooded timber. Sensitive fathometers are indispensable aids in finding prime deep winter striper structures, and allow for “seeing” fish, too.

Many winter striper anglers employ downriggers even when “fishin’ the jumps.” Often the smallest stripers are the ones churning the surface gorging on top-side “jumping” shad. Often the biggest stripers are deep, under small fish. Getting a lure through small linesiders to big ones can be difficult. But trolling baits and lures deep and under the little stripers with downriggers is deadly effective for heavyweight fish.

Water temperature is a major influence on striped bass location. Stripers are most active in the 50 to 65 degree range, which is common on many open-water impoundments during winter.

During the coldest months of winter, forage-fish schools actively seek warmer water temperatures. For this reason, there generally is an “up-reservoir” movement of bait schools because headwaters of most lakes are the shallowest, and therefore warm quickest during favorable winter weather conditions. Too, headwaters of many reservoirs have a constant influx of comparatively warm river or spring water – which bait schools seek for survival.

Naturally, where bait goes, so follows stripers. So during winter, the mouths of major feeder creeks in the “upper,” more shallow regions of reservoirs are outstanding places to catch linesiders. Mid-winter stripers frequently are found lurking below massive bait schools that have migrated to headwater regions of reservoirs. In creek coves, slow trolling with downriggers, drifting with live baits, and vertical jigging are all productive. It’s important, however, to imitate the forage fish present as closely as possible – not only to color, but size as well. If baitfish are 3-inch long shad, for example, silver, deep-body lures of that length invariably produce not only more stripers, but bigger ones, too.

In the coldest months of winter, it’s common for baitfish schools to migrate into very shallow creek arms, often in water just a few feet deep. The bait moves into creeks seeking warm water, which is heated by sunny, mid-day temperatures. Early winter and late winter days that may reach into the 40s, 50s or warmer, are prime for stripers.

Stripers are reluctant to move into such shallows during bright, daylight hours, however, since they are among the most light-shy of all gamefish species. But during low-light conditions, stripers can be counted on to migrate into the shallows where they’ll gorge on hapless schools of warm-water seeking bait.

Keeping a sharp eye out for dead or dying baitfish is a key element in locating big winter stripers on many waters. Sometimes in winter threadfin shad in impoundments die by the thousands due to cold winter water temperatures. Anglers who fish areas of reservoirs where shad are dying en masse commonly enjoy some of the best action of the year for outsize linesides. Frequently, the shad and stripers are found in water less than 10 feet deep.

Naturally, the shallower the water the more likely it is that prime fishing will be had during low-light conditions. Live shad fished with a split-shot and cork float can be deadly for stripers in areas where shad are stressed and dying from cold water. At times, anglers can dip net dead baitfish and catch stripers with the dead baits. Usually the baits are best when drifted deep, off points and other structures near where the forage species are found dead. Slow-trolled, shad-imitating plugs (Shadling, Shad Rap, Cordell Spot, Rat-L-Trap) lightweight white marabou jigs (Lindy’s Fuzz-EE-Grub is a personal favorite) also are favored by many anglers when working areas where shad are dying.