by Bob McNally

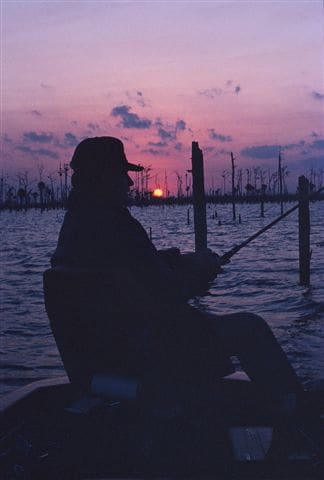

On a December night as dark as a witch’s heart, the boys on Bull Shoals Lake were “slow-rolling,” and they had a boat full of bass that would make any angler proud.

Slow-rolling is a technique that has been catching largemouths for decades, and it’s still productive today.

It was the era before electric motors and depth finders. Some rods were still made of steel and split-cane. And fish stringers were in vogue, not livewells.

The boat was small and aluminum, with sharp, V-angle sides. The outboard on the stern was the latest model – an old round-top Evinrude. Sitting in the stern, at the tiller handle, was Forrest Wood, back in the days when he was still a guide in Flippin, Ark. Bass boats with steering wheels and the name Ranger Boats were not yet a twinkle in the eye of the guide with the Stetson hat.

Sitting in the bow of the boat was my father, Tom, and at age 9, I felt pretty grown up fishing at midnight on the sprawling Arkansas reservoir with a pair of well-known and very successful bass fishermen.

But the thing I remember most about that after-hours Christmas fishing trip back in 1959 was the number of bass we caught – and their size. It seemed like someone aboard our little skiff had on a fish every 20 minutes or so, and all of them were huge by the bassin’ standards I’d learned growing up in the Upper Midwest. The fishing technique seemed strange to me, too. Never before had I fished lures the way Wood said would work, and work they did.

It wasn’t until the next morning in the dazzling sunshine when I inspected our enormous stringer of bass that I realized what an incredible night of cold-water fishing we’d had. Attached to the floating boat dock near the old and famous Crow Barnes Resort was our night-caught bass stringer, and I still remember I couldn’t half lift it from the lake’s clear waters. But I ogled those fish for hours that day, and it was hard for me to believe I’d been part of their catching process. There were nearly two dozen largemouths, all between 3- and 6-pounds. More and bigger bass than I’d ever been around, and it was all because of the “slow roll,” as Forrest Wood so simply called the fishing technique that duped those lunkers.

Instead of casting big plugs to shoreline cover or weedless spoons to lily pads, which was standard practice in that era of bass fishing, Wood had us cast large 1/2-ounce black jigs to rocky points of land. All night we cast toward the points, while Forrest kept the skiff in deep water. The key to working the jigs, I remember him saying, was to fish ‘em slow, just rolling the lures along bottom. He said it made the jigs look like bottom-hugging crawfish and other forage Bull Shoals bass wanted.

We used ball-head jigs, most made of bucktail, but some had marabou dressing, and a few I recall were tipped with all-black Uncle Josh pork-rind eels. But no matter what the refinements in the lures were, the essential element in the success of the jigs was they were rolled meticulously down the sides of submerged rocky points, right along bottom, then pumped ever-so-slowly back to the boat. Most of the strikes came as the jigs crawled over rocks and gravel of Bull Shoals’ points. But some fish hit in the last half of the slow roll, when the lures had reached their deepest level and had started the long retrieve up to us in the boat.

I remember being amazed that fishing black jigs at night along bottom was so effective in catching bass so far from shoreline cover that most fish I’d caught previously were taken. Also, we worked the lures so slowly I thought back then that Bull Shoals bigmouths must have been unique in their feeding preferences. Naturally, that Bull Shoals bassin’ trip had little bearing on my youthful fishing on my native waters when I returned home to Illinois. I kept right on casting surface chuggers and “River Runts” to shoreline cover, and I caught my share of bass just like everyone else.

It wasn’t until I was a teenager, again in Arkansas, that the significance of slow-rolling finally sunk in. It was December, again, and I was with college friend Tim Sampson on Norfolk Reservoir. All the locals we learned were fishing at night using plastic worms, and working them slow and deep off points. Memories of fishing with Forrest Wood and dad instantly came to mind, and by fishing the exact same way we had on Bull Shoals, only using the “new” breed of plastic worms, Sampson and I enjoyed outstanding fishing on Norfolk. From Norfolk we traveled west and north to Table Rock Reservoir, and though none of the resident anglers were fishing at night, we scored well by slow-rolling worms after the sun set.

We knew we were on to something, and we brought back the technique to Illinois, and discovered it was deadly on many of the winter bass waters we both knew well. We found we caught plenty of bass slow-rolling even during the day. The tactic produced big largemouths in southern Illinois at rocky and deep Devil’s Kitchen Lake and on sand-bottom Crab Orchard Lake. Slow-rollin’ also scored on smallmouths for us on clear, deep tough cold waters like southern Wisconsin’s Lake Geneva and Grindstone Lake in the northern part of the state.

Spinnerbaits are great for slow-rolling, especially in the winter months and the early spring when bass are hugging the bottom on deep points and flats.

As the years went by, the arsenal of successful lures we used slow-rolling grew to include big, heavy, single-blade spinnerbaits. Ball-head spinnerbaits were best because they fouled less on bottom than other head designs. And while willowleaf and Indiana-blade baits were okay, a large number 4 or 5 Colorado blade was tops because it thumped greatly during the slow-roll retrieve, and thus telegraphed its action nicely up the line and rod to our hands. Any break in the rhythmic thumping of the spinnerbait during the slow-roll retrieve signaled a strike.

In more recent years, I’ve learned that quality and sensitive graphite rods s an important asset to the most successful slow-rolling because of the superb feel an angler has during the lure retrieve. Also, I’ve learned that when deep, clear waters are fished, particularly for smallmouths, lures as light as 1/8-ounce, used with spinning tackle and 6-pound line, can be slow-rolled with remarkable success.

Another modern twist to slow-rolling has been modern braided lines. New, fine and ultra-sensitive braid allows lures to sink fast with a tight line, and with little line stretch lure “feel” and strikes from fish are greatly improved. One side note, with braid, anglers should use a stiff fluorocarbon leader about 20 inches long. This helps avoid limp braided line fouling in a spinner-bait’s hardware.

Slow-rolling has produced winter Kentucky bass, as well as stripers and even white bass for me in 30 years of using the technique.

Like most fishing tactics, the slow-roll isn’t productive through all seasons of the year. It’s most effective during winter and again during the broiling days of summer, times when bass commonly are deep. Submerged points are among the most productive places to practice the slow-roll. Deep points having stumps, sunken brush piles, and creek channels along their drop-off edges are ideal places to slow-roll lures. Many other good bass-holding structures can be fished using the technique, too.

Weedless, single-blade spinnerbaits cast parallel to riprap edges and slow-rolled over rocks and debris along bottom is sure to get the attention of bass living and feeding in an area. A slow-rolled jig bumped around a bridge support once produced a 19-pound striped bass from Florida’s St. Johns River while I was fishing for largemouths. And I’ve caught plenty of marine fish using the same technique, including redfish, flounder, snook and tarpon.

One time on a deep, rocky hump on Ontario’s Lake Manitoumeig, I took a 5-pound smallmouth while slow-rolling a Mann’s Big George. Heavy tail-spinner lures now have been included in my personal arsenal of slow-rolling artificials.

On clean or sandy bars, humps and points, I’ve had good success slow-rolling heavy spoons, which tumble and flash as they’re rolled and look much like an injured baitfish on the bottom. Northland’s Forage Minnow spoon is a personal favorite, as it has an oversize treble hook, ideal for big bass and other species. Last winter while probing deep shell bars with Forage Minnows I caught a staggering number of large channel catfish while looking for largemouth bass. That’s right, catfish, and some weighed to 10 pounds.

Rocky ledges are another great structure for slow- rolling. Not only does the technique catch bass (especially Kentuckys and smallmouths) that are holding in and near crevices of the ledge itself, but during the last half of a U-shaped, slow-roll retrieve, suspended bass frequently are caught. These bass of the third dimension can be among the most frustrating to locate, but often a slow-rolled lure will find a suspended school of fish. Once such bass are located it can be a pretty simple matter to catch plenty.

While proper feel is important in most bass fishing, it’s vital to success when slow-rolling. A good, sensitive graphite rod helps, as previously noted. But an angler also must make a conscious effort to keep a tight line throughout the slow, bottom-hugging retrieve. Having a tight line at all times helps telegraph what the lure is doing during the retrieve, and this aids in detecting strikes. This is why braided line is so helpful.

Sometimes the “buggier” looking a lure the better it is for slow-rolling. Thus many of the larger, crawfish-style bass flippin’ jigs work well. Grub jigs, plastic worms, lizards and “creatures” (made of plastic, hair or feathers) in many sizes, shapes and colors are great for slow-rolling. Pork rind or soft plastic trailers such as Berkley GULP can be used on many lures to enhance them.

Instead of imparting action to the lure as many anglers do when using other techniques, a slow-rolled lure should just be bumped or tight-lined along bottom. The reel handle is turned ever-so-slowly. Sometimes a slight hop can be imparted to a slow-rolled lure (best with tail-spinners and spinner-baits), but it’s best to be judicious with such action in cold water. Simply wiggling a rod’s tip slightly will send vibrations down a braided line, which will seductively twitch a slow-rolled lure.

When retrieving a slow-rolled artificial, keep in mind what Forrest Wood explained to me so many years ago. He said bottom-bumping lures were meant to imitate crawfish and other critters inching along a lake or river floor. Remember that, and imitate such forage action during a retrieve. Done correctly, it’s almost a sure bet the time between strikes will be less for slow-rollers during those tough fishing days in summer and winter.

The Union Sportsmen’s Alliance website is designed to provide valuable articles about hunting, fishing and conservation for members of AFL-CIO affiliated labor unions and all sportsmen and sportswomen who appreciate hunting and fishing and want to preserve our outdoor heritage for future generations. If you would like your own story and experience from the outdoors to be considered for our website, please email us at [email protected].