Okay, the word is actually “reticule.” You won’t get the word “reticle” to come up on your spell-check. But over the years, in our little world, we’ve shortened it to “reticle.” Whatever you call it, it is the arrangement of aiming point or points that you see when you look through your riflescope.

Perhaps the most common is some form of “crosshair.” That word actually comes from a time when actual hairs were crossed inside the scope to create an aiming point. More common, at least in hunting scopes, was a very bold post…and then there were centered dots suspended on crosshairs, and a whole lot more.

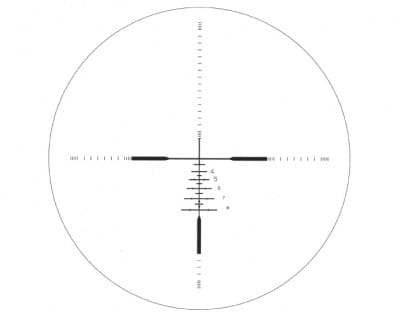

In riflescopes technology is a wonderful thing. Reticles are no longer hairs that frequently break (although some modern reticles can break!), and we have lots of options. The basics of choosing a reticle are very simple. The finer (smaller) the intersection of the crosshairs, the more precise the aiming point because a smaller amount of the target is subtended (covered) by the reticle itself. On the other hand, the finer the crosshairs the more difficult they are to pick out in low light, and the slower it is for the eye to pick them up.

This is am obvious dilemma, and it means that the ideal reticle for small varmints at long range is not equally ideal for big game up close in low light. For the former, a very fine crosshair (literally the size of a hair) that allows you to see through the intersection and establish an aiming point on a prairie dog at 300 yards is ideal. For the latter, you want a bold, bright aiming point that centers your eye instantaneously, and it isn’t really important if that aiming point covers a bit of the target.

Historically, the fastest aiming point was a bold dot. That’s a reticle from a previous generation, but I used it a bit many years ago, and I’ve never seen anything faster on moving game. The old Lee “two minute dot” covered two inches at 100 yards, so at longer ranges became difficult to use because it covered so much of the target…but the eye is naturally drawn to that big dot, making it very fast. Another popular old-time reticle that is still seen today is the post, or post with horizontal crosshair. This is also a very fast reticle, but it does take a bit of familiarity. Do you put the post at six o’clock, or do you cover the aiming point with the tip of the post? Both work, but it depends on how you sight the rifle.

Leupold pioneered the Duplex reticle. This has become the most popular of all reticles, and it does indeed offer the best of all worlds. The outer wires are thick, thus quick and easy to see, but the inner wires are much finer, offering a precise aiming point. Almost every scope manufacturer today has some “plex-type” reticle, and it really does offer an ideal solution for the majority of shots under the majority of conditions.

There are two advancements that have taken things a step farther. Today’s lighted reticles solve the historic problem of the inability to see the center in low light, or against a very dark target. A lighted center draws the eye to the center, allowing more precise shot placement in poor light, and faster target acquisition in almost any light. Several years ago I was introduced to Trijicon’s scopes with the tritium-lighted reticle, essentially a lighted reticle without the battery. Their post reticle with tritium-lighted tip is truly marvelous at closer ranges, and I’ve learned that, the more I use it, the wider the range envelope becomes.

Even so, no post reticle is a long-range reticle because, as holdover is required, the post covers too much of the target. For that matter, no standard crosshair reticle, including a plex-type, is well-suited to long-range shooting. As holdover become necessary, you really need a reticle that offers additional aiming points for longer ranges. There are all kinds of systems, from “mil-dot” to additional stadia lines to circles like the Nikon system. And then there are adjustable turrets that allow you to “dial in” the range with the help of a rangefinder. All work, and all work fairly well…but it’s essential that you spend time at the range and figure out what the values mean for your rifle and your load at actual distances. Factory specs and guesswork aren’t good enough; for long-range shooting you must verify the data at actual ranges.

I have my favorites, of course, but I’ve played with most systems: Swarovski’s TDS, Zeiss’ Rapid Z, Leupold’s Boone and Crockett reticle, and Nikon’s circle-system; and standard mil-dot reticles from Trijicon, Springfield, Premier, and others. All work. Some are more precise than others, but it depends on the ranges you expect to encounter. The common thread is you simply must spend time at the range, in actual shooting situations, both validating the values of your aiming point and becoming familiar with how to use them.

Personally, I’m a stadia-line guy. I’m very comfortable with additional aiming points, but have the most familiarity with simple stadia lines like Leupold’s B&C reticle or Zeiss’ Rapid-Z. I never actually learned how to use a mil-dot system, so when I intended to use Trijicon’s 5-20X (with tritium-lighted reticle, truly the best of all worlds!) I needed some help. I went to SAAM marksmanship course in the Texas Hill Country, and they worked me through it. Given time, I could have figured it out on my own but, like many of us, that kind of time wasn’t’ available. There are two lessons here: First, it does take time to properly learn any range compensation reticle. Second, if you don’t have time, the only shortcut is to get some help!