The buck was standing on the edge of the treeline, just his head and antlers visible. He wasn’t a monster, but from his head shape and antler mass I knew he was an older buck. And my season was running out fast. I picked up the rifle, and through the scope I could see a small spot of shoulder through dry leaves. The rifle made its flat little crack, and the buck lurched forward, running across a narrow opening into the next treeline. I could see him clearly through bare trees, but there was no reason to shoot again. He made maybe 50 yards, then faltered, fell, and was still.

The buck was standing on the edge of the treeline, just his head and antlers visible. He wasn’t a monster, but from his head shape and antler mass I knew he was an older buck. And my season was running out fast. I picked up the rifle, and through the scope I could see a small spot of shoulder through dry leaves. The rifle made its flat little crack, and the buck lurched forward, running across a narrow opening into the next treeline. I could see him clearly through bare trees, but there was no reason to shoot again. He made maybe 50 yards, then faltered, fell, and was still.

Both the rifle and the cartridge I used are among my all-time favorites. The rifle, though not important to this discussion, is a lovely custom job built by Texas riflemaker Todd Ramirez. It’s on a left-hand Mauser action, and is built along the lines of a 1920s “stalking rifle.” This makes it a perfect match for the cartridge, the great old 7mm Mauser, to my thinking one of the very best of all of our whitetail cartridges-and not bad for a whole lot of other things.

Developed by Peter Paul Mauser in 1892, the 7mm Mauser is the oldest cartridge still in common use that was developed for smokeless powder. In 1893 the cartridge and its Mauser rifle were adopted by the Spanish military, with several European and Latin American countries following. The British were introduced to the cartridge during the second Boer War, where, in the hands of Afrikaner marksmen, it seemed far superior to the slower .303 British cartridge. Americans learned about it at the same time, in Cuba in 1898. We won the Spanish American War very quickly, but at a price: Spanish troops with their 7mm Mausers inflicted terrible casualties on the attacking Americans, many of whom were still armed with trapdoor Springfields.

The end flaps of most American factory loads for this cartridge identify it simply as “7mm Mauser,” which is certainly correct, but I tend to prefer the proper European title of “7×57,” which identifies it at a 7mm cartridge, bullet diameter .284-inch, with a case length of 57 millimeters. As the 19th Century turned to the 20th Century the old London firm of John Rigby was Mauser’s exclusive agent in England. Neither name was adequate, so for the British gun trade the cartridge was renamed “.275 Rigby,” following the British convention of naming cartridge by land diameter rather than groove diameter.

By all three names the cartridge was a worldwide standard hunting cartridge for many years. Jack O’Connor, famed as the champion of the .270 Winchester, did a lot of his early hunting with the 7×57. His wife, Eleanor O’Connor, an accomplished huntress in her own right, used the 7×57 almost exclusively throughout her long career. Jim Corbett, famous hunter of India’s maneaters, generally used a .400 Jeffery for tiger and thick-skinned game, but he used his .275 Rigby for most of his hunting.

Walter Dalrymple Maitland “Karamoja” Bell was perhaps the most famous fan of the 7mm Mauser. Bell was a successful ivory hunter in the early 20th Century, and after his retirement to Scotland he proved a wonderful storyteller, leaving us books that remain classics to this day. It is not true that he used his .275 Rigby to take the 1000 elephants he is credited with. He used several “small bores,” as they were called then, including the 6.5mm Mannlicher and .303 British. His biggest bag was taken with a medium bore, the .318 Westley Richards (actually a .33 caliber), and on his final expedition he used a .400 Jeffery. But it is true that he took many elephants with his 7×57, once writing that the barrel of his .275 Rigby “was never polluted by the passage of a softnosed bullet.”

The load used by Bell was either the original military load featuring a 173-grain round-nosed, full-metal-jacket bullet at about 2300 feet per second; or a similar commercial load with a 175-grain steel-jacketed “solid.” With moderate velocity and that long-for-caliber bullet penetration was (and is) spectacular, far superior to the large-caliber blackpowder cartridges the new smokeless cartridges replaced African hunting has changed, and today we accept that, despite its great penetration, the 7×57 falls far below the sensible (and legal) minimum for really large game. With lighter, faster bullets, however, it remains a wonderfully useful hunting cartridge.

The 7×57 was an original chambering for the Winchester Model 70, and over the years has been chambered now and again in most American factory rifles. Here in the United States it can no longer be considered popular, but it’s a cartridge that refuses to die, and during its long history has made several comebacks. It does have drawbacks. Factory loads are limited, and because of concerns about its use in century-old original rifles, most current loads are very mild. Most available is a 139 or 140-grain bullet at standard velocity of 2660 fps. This is not impressive by today’s standards, but at that moderate velocity bullet performance is consistently wonderful, with very little recoil and a distinctively mild report.

Handloaders can increase the velocity by a considerable margin, and Hornady’s Light Magnum load, now discontinued, propelled their 139-grain bullet at 2830 fps. The obvious comparison is to the 7mm-08 Remington, which has a shorter case but with much less body taper. As a newer cartridge, absent concerns about pre-1900 rifles, the 7mm-08 is loaded considerably hotter, with standard 140-grain loads at 2860 fps. Also, as much as I hate to admit it, in my experience the 7mm-08 tends to be a more accurate cartridge. I have actually never seen a 7×57 that was a real tackdriver, although I’m sure there must be some out there!

None of this bothers me. I don’t consider the 7×57 or the 7mm-08 to be long-range cartridges, and the several 7x57s I’ve owned and used have been plenty accurate for the 250-yard range envelope I try to keep the cartridge within. The 7mm-08 has supplanted the 7×57 in popularity, and has a much greater range of factory loads available. Both of them, however, are incredibly effective hunting cartridges, performing far beyond what their paper ballistics might suggest. I freely admit that I got my daughter a 7mm-08-but I cling to the 7×57, at least partly for nostalgia.

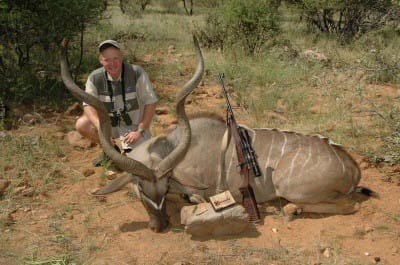

I’ve done a lot of whitetail hunting with the cartridge, not in big, open fields, but in woods and mixed cover. I haven’t elk with it, but I certainly would. I have, however, used it for a tremendous variety of game elsewhere in the world. I’ve used 7x57s in Africa, Europe, South America, and the South Pacific as well as North America. On the smaller end, the cartridge has accounted for red stag in New Zealand, greater kudu in Africa, roebuck in England, hog deer in Australia, and the list goes on. One perhaps silly thing I did that sure was fun: In 2008 I took my 7×57 to Santa Fe Province in northern Argentina. During the trip I would hunt brocket deer, peccary, capybara, wild boar, and so forth-but I only wanted to take one rifle, and I would also be hunting water buffalo.

I had Larry Barnett whip up a box of 7×57 ammo with 175-grain Barnes Super Solids. The water buffalo is, perhaps, not quite as aggressive as Africa’s Cape buffalo-but he’s a whole lot bigger, with genuine weights up to perhaps 2300 pounds. We took a lot of time crawling up on a monstrous bull, and when we got in close that little 7×57 suddenly felt awfully small! But now I was committed. With his head quartering toward me I held halfway between his eye and the base of his horn, and that little bullet dropped him like a rock-just like it did for Karamoja Bell a century ago. It worked, but in the future I think I’ll stick with game the 7×57 is better suited for. There’s a whole world of it out there!