Brad Crosby, Professional Hunting Guide

The afternoon we rode into camp, the weather started to change. During first rifle season in New Mexico, the weather always turns, from good to bad or bad to worse. I met Stewart at the trailhead with the rest of the hunters. My first impression was that I had a tough and ready hunter. Stewart had put in for this for six years, and this was going to be the last. You see, Stewart was 72-years-old, and he knew the Gila Wilderness was going to be tough.

The afternoon we rode into camp, the weather started to change. During first rifle season in New Mexico, the weather always turns, from good to bad or bad to worse. I met Stewart at the trailhead with the rest of the hunters. My first impression was that I had a tough and ready hunter. Stewart had put in for this for six years, and this was going to be the last. You see, Stewart was 72-years-old, and he knew the Gila Wilderness was going to be tough.

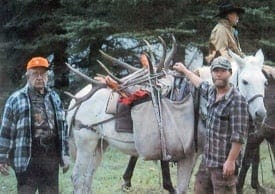

We had six hunters, six guides, a cook, a wrangler, and 21 horses and mules. By the time we had the mules unloaded, the rain started. The next morning, it got heavier, and the wind was blowing sideways – not prime weather for elk hunting, but that didn’t phase Old Stew.

As we headed out in the dark and made our way up the pass, sheets of rain walloped across our horses. I kept looking back to make sure Stewart hadn’t been blown off his horse. There he was, hunkered down ten paces behind me, scanning the morning dawn for the Elusive Wapiti.

Nothing was at the pass but wind and rain, so I figured we needed to head deeper into the timber. Elk are no dummies; they too were seeking shelter from the storm. We moved into the next drainage and worked our way up the draw to a ridge where I knew the elk had been bedding. Two cows crossed in front of us, and we held up to see if a bull was close behind. No bull, so we kept moving up the draw scanning for horns and hide.

We reached a rolling ridge thick with grass and ferns, prime elk country, but a thick wall of clouds was moving in fast. We’ll go on, I thought, roll off the nose of this ridge and ride through the thick dog hair to the north. Just as I was making my way up the ridge, I heard the “snap” and “crack” of a tree giving to the wind. According to an old-timer in the Gila, there are three things to be scared of: lightening, yellow jackets and wind. And when you hear the “pop” of a tree, you better look to see where that son of a gun might be landing.

As quickly as I heard the pop, I lifted my eyes from beneath the soaked brim of my hat and looked for the tree. Straight above me, the trunk of a huge Ponderosa Pine was falling directly down on my mule and me.

As I realized this tree was heading straight toward us, my mule, Clifford, figured it out too. He leaped three feet to the left, landing on top of two other downed trees, just escaping the mighty Ponderosa as it whizzed by. While Clifford reared and leaped, I turned to see that the tree was now crushing down on Stewart and his horse, Bud.

Branches scattered. A white horse fell to the right, and the orange of Stewart’s hat and vest disappeared under the cloud of debris. I jumped from Clifford and ran to Stewart. When I got there, I saw a tree branch through the head of the horse. Bud was dead. Stewart was lying face down, alive! He was moving. His foot was caught underneath the dead horse. I told him to move slowly. I got his leg free and helped him to his knees. He was covered in blood but whose? After checking his head, neck and back and running through a first responder checklist, Stewart seemed to be, miraculously, in good shape. The tree just fell on him, the horse was dead and Stewart came out of it scratched, bruised and stunned more than anything. As we descended to a safe area, I noticed Stewart’s left hand swelling and turning black and blue.

Branches scattered. A white horse fell to the right, and the orange of Stewart’s hat and vest disappeared under the cloud of debris. I jumped from Clifford and ran to Stewart. When I got there, I saw a tree branch through the head of the horse. Bud was dead. Stewart was lying face down, alive! He was moving. His foot was caught underneath the dead horse. I told him to move slowly. I got his leg free and helped him to his knees. He was covered in blood but whose? After checking his head, neck and back and running through a first responder checklist, Stewart seemed to be, miraculously, in good shape. The tree just fell on him, the horse was dead and Stewart came out of it scratched, bruised and stunned more than anything. As we descended to a safe area, I noticed Stewart’s left hand swelling and turning black and blue.

“Okay Stewart, we are going to have to get back to camp, get another horse and get to the hospital,” I said.

“Hospital?” Stewart exclaimed. “I don’t need to go to the hospital. It’s eight in the morning. We should hunt the rest of the day and see how it goes.”

On one hand, the guy had waited six years to hunt the Gila. On the other hand, his hand might be broken. My first instinct was to get this 72-year-old into better medical hands, but the decision was his.

“We’ll hunt the rest of the morning and see how the hand does,” I agreed.

His hand got worse. It was obvious it was too difficult to even hold his rifle. I told him to get on the mule, and I would walk back to camp.

“No. It’s four miles back to camp. I’ll stay here and maybe an elk will come by. You take Clifford back to camp, get another horse and come back for me,” Stewart said.

It took three or four hours to get back to where I left Stew. I brought an extra horse and one wrangler. We put Stewart on Clifford and the wrangler took him back to camp. The next morning was calm as we started the nine mile ride to Stew’s truck at the trailhead. It was a half-day ride from the trailhead to the main road then two more hours to the hospital in Silver City.

We arrived at the emergency room late that afternoon. The x-rays showed three broken bones in the left hand, a fractured wrist, massive contusions down his left side and a bruised left ankle. The nurse and doctors were fascinated. Falling trees, a dead horse, a 112 mile ride to the hospital. This old guy had one close call.

“What do you want to do next Stewart?” I asked. “Are you hungry?”

“Yeah, let’s get something to eat. Then we can head back,” he replied.

“Head back?” I asked. That didn’t surprise me. Of course, we were heading back, but “tonight?”

Stewart already had the plan. We would head back to the horses, sleep at the trailhead and be ready to head out early the next morning. And we did just that. At camp, everyone was surprised and excited to see Old Stew back so soon. Can’t keep a good man down, I guess. The next morning was calm and cold. Tom Klumker, the owner of San Francisco River Outfitters, asked Stewart if he thought he would be able to go ahead with his hunt.

“Give me five minutes,” Stew said. He walked to his tent, picked up the rifle, dry fired it twice, came back and said, “Tom, my fingers move enough. I can squeeze the trigger. I’ve waited six years for this and there’s no stopping me now.”

We planned to head to the top of the mesas to the south. Our route was steep and long, traversing up from the river bottom along the east side of a rocky cliff. Close to the summit, we came across a landslide. I turned to Stewart who was on Clifford ten paces behind me with a trigger finger modified cast resting in a sling. He smiled and asked if I needed help clearing a path for our horses.

An hour later, we were through the slide and heading to the top of the mesa. The sun was brightening the day, and it was starting to look elky! Then there they were, 15-20 elk meandering 250 yards out. I signaled to Stewart, as I slipped off my horse and moved to the scabbard side of Stewart’s mule. He slowly and painfully lowered himself to the ground. I took Stewart’s rifle from his scabbard, chambered a round and handed it to him saying, “the rest is up to you.”

We moved slowly from one tree to the next, cutting our distance in half. Behind a small stand of trees, two bulls were pushing cows back and forth. The sun was creeping over the ridge, silhouetting the animals. I told Stewart to get a bead on one of the bulls and keep it there. “Got ‘em,” Stewart said. He followed the bull back and forth while he rounded up his herd. The bulls were still behind the stand of trees and oblivious to everything other than cows.

I let out a series of cow calls. The bulls went crazy. Both turned and headed straight for us. They stopped short of coming out from the trees. One more cow call and the bull Stewart had a bead on stepped out. At the same time the bull cleared the trees, he let out a screamer of a bugle. Mid-bugle, Stewart anchored his 338 the best he could with his cast, pulled the trigger and dropped the bull to the ground. The single neck shot severed the bull’s spine, killing him on the spot.

I let out a series of cow calls. The bulls went crazy. Both turned and headed straight for us. They stopped short of coming out from the trees. One more cow call and the bull Stewart had a bead on stepped out. At the same time the bull cleared the trees, he let out a screamer of a bugle. Mid-bugle, Stewart anchored his 338 the best he could with his cast, pulled the trigger and dropped the bull to the ground. The single neck shot severed the bull’s spine, killing him on the spot.

Stewart, needless to say, was pleaseed. His 310 Gila bull had become a hunt of a lifetime. Stewart left the Gila with not only his bull but a slew of stories and a lifelong friend. What a hunter!

After returning to the site where the tree fell, it became obvious what had happened. When the tree was falling, Stewart had unknowingly slipped between the crotch of a branch and the trunk of the tree. One side of the tree scathed Stewart, stripping him from his horse, while the other branch went directly through the horse’s head. There was no room for error. When hitting the ground, the tree left a three-inch depression, then bounced two feet away from Stewart’s head. Any change in the series of events that lead up to this moment might have resulted in a far more serious situation. It’s still unreal that Stewart lived to tell about it. No kidding, this really happened.